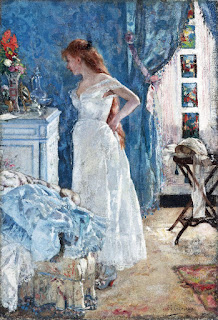

Henri Gervex: Le Bal de l’Opera

Henry Gervex made his name during the 1880s as one of the boldest of the young artists who took Parisian social life and fin-de-siècle manners for their focus. In Le Bal de l'Opéra, painted in 1886, Gervex combined an immediately recognizable venue, the luxuriously grand foyer of Garnier's new Paris Opéra House, with an even more distinctly French social event, the masked balls that enlivened the winter season and fascinated French and foreign audiences alike. With his dramatic cropping of the foreground figures (which brings the viewer right onto the famous Opéra staircase amid the departing revellers) and his strategic emphasis on the pervasive black suits, top hats and walking sticks of his stylish male figures, Gervex deftly acknowledged the Impressionist example of his close friends Manet and Degas. At the same time, his complex staging of intriguing story lines and careful attention to architectural details kept Gervex and the risqué subject matter of Le Bal de l'Opéra within the expectations of the still powerful academic establishment. [Galerie Heim]